Igor Ponosov (RUS): Artist, curator, researcher, author and publisher focused on Urban Art since 20 years

Hi Igor, you published many books since 2005. In your book from 2018 Russian Urban Art: History and Conflicts, you wrote you started being interested in Hip Hop culture in 1996, with the age of 16. Can you tell us how you discovered this culture, graffiti writing and what exactly did attract you at that time?

I got interested in Hip Hop culture through music, it was in 1996, I guess. As a teenager, I enjoyed different styles of music like punk, hardcore metal and breakbeat, but especially Russian rap which was getting popular at that time. I was born and grew up in Nizhnevartovsk, close to Siberia and far from Europe. After USSR fall in the 90s a part of western culture (music and films) arrived in a DIY way: for example, you could watch American movies like Terminator or Robocop in small wagons/containers on a TV screen, viewings that were organized by cooperative business, so new in Russia. Self-made cassettes with music were produced by individuals, with black and white cover printing in a fanzine style. It was a grassroots culture somehow and very interesting for young people.

Did you start with graffiti writing yourself? (When, with what name and where?)

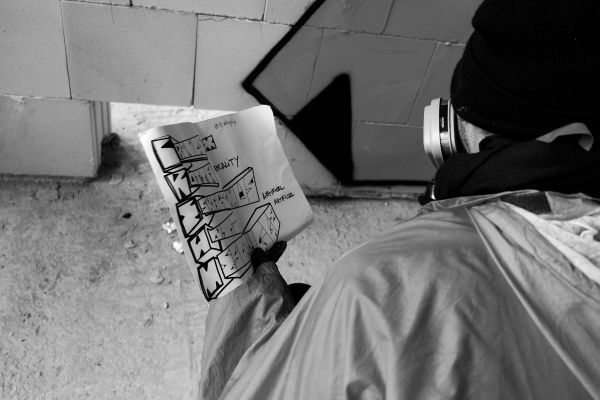

In my childhood, I spend time in a small town in the north. In 1999, I moved to Kyiv, where my grandparents lived. I spend a couple of years there and got inspired by the local graffiti scene, and tried my first experiments on the wall, but not very often. In 2003, I moved to Moscow and continued to do graffiti writing, but I was not so good with that, I had a few nicknames like Mos67, Dokas and Borro. But soon I got bored from nicknames and style writing and changed my practice towards street art. In 2004 until 2007, I made pixel art, posters and stickers in the streets. In 2008, I had my first performance („Red cube“) which completely changed my practice. I started to do social engaged, conceptual and performative works, and worked interdisciplinary.

Did you study art?

No, I’m kind of self-educated person, and actually I learned in an organic way through graffiti and hip hop as grassroots and through self-organized culture. But my interest focused not only on urban culture, I am impressed by interdisciplinary contemporary art, activism, performances and conceptual practices. I have a big library focused on different art practices and for me, it is more important than just theory which you get at University. Anyway, I never had time for studies, because I always had many ideas for new projects and books. I just didn’t want to spend time sitting inside but wanted to be active.

When did you start your artistic practice, involving outdoor interventions and creating studio works?

My first real public intervention happened in 2008. I did a performance which was a real challenge as that time, because before I was working in the streets at night anonymously. In 2011, with my friend Make, we organized Partizaning movement. We realized together many social engaged and participatory interventions in Moscow, in some institutions in Russia, Europe, US and Brazil. There we participated in different activities, it was impressive and a very important time for me. I never thought about my studio works and gallery projects, it was so boring for me to do something for a white cube. But in 2019, I got my first studio in Moscow. Since then, I created some works based on found materials which I kept from my different outside projects, like banners, mainly old advertisements.

You published three books about Street Art in Russia between 2005-2009. Can you tell us how your first book project came up, and what was the content?

When I moved to Moscow in 2003, I was bored about graffiti after a while because it was so similar to classic styles without any message for an audience. I started to think about building a kind of Street art community in Russia. In 2004, I launched a website called Visualartifacts.ru where I published interesting graffiti experiments from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. I was inspired by Ekosystem.org and tried to do a similar online platform for local street artists. In 2005, I decided to publish a book, and it was my first experiment with book design and publishing. Visually my book was close to a zine or a booklet, it was a good start to do series of editions. I learned fast and published two more books called Objects book in 2006 and in 2008 with 3000 copies. My book series was a first print edition focused on the Russian street art scene, featuring some artists from Ukraine and Belarus. Actually, my editions are now an archive about the beginnings of Street art in Russia and available at the archive of GARAGE, Museum of Contemporary art in Moscow: russianartarchive.net/en/catalogue/document/P3721

From 2011 to 2013 you curated The Wall a project based in the CCA Winzavod, Moscow. On your website you describe it:“ It was an open exhibition ground, a kind of debating-society, where internal and external problems of graffiti culture were made actual. Besides displaying separate works, artists and trends, every new exhibition should be an argument or a narration devoted to special cultural processes and practices of street art as well as to street art in general“. How big was this project at that time, with which artists did you work? Can you name some internal and external problems of graffiti culture back then?

In 2011, my friend Kirill Kto, a Moscow based conceptual graffiti artist, invited me to curate The Wall project. Not only for painting a wall which was located in the art centre. At that time, street art was not part of the contemporary art scene, and we had no public discussions about graffiti and street art. We decided to organize a discussion club about different topics with the exploration of history in different perspectives, experimental practices and activism. During 2,5 years we organized more than 30 artist talks, lectures and discussions. It was a very important project for the research about graffiti and street art, because we tried to find another perspective of developing our practice.

In 2011, you founded the Partizaning art project as a platform for exchange among activists, artists and urbanists. Can you describe the activities and results of that project, and is it still going on?

It was at the same time while curating The Wall project. With Make, an activist and Moscow based graffiti artist, we organized Partizaning as a movement. First we started a website as a platform describing many street actions around the world. Partizaning.org was an online media with our critical reviews about Russian projects (exhibitions, festivals, urban planning), but also, we published our vision to improve cities by self-organization. Our main idea was focused on Henri Lefebvre’s idea of “Right to the city” which we understood as the base of democratic values in the urban context. As a group in 2011 until 2014, we made many urban interventions to declare that vision.

How many people are participating in Partizaning? What kind of people?

Hard to say, because the movement was kind of an open source, but mainly we had people with an artistic background, urban planners, sociologists, activists, guerrilla gardeners. It was a very interdisciplinary community.

In 2016, you published the book Art and the city (2016), for which you received The Sergey Kuryokhin Contemporary Art Award 2016 for Best Text on Contemporary Art (St. Petersburg). How long did you work on that book, and what is special about this publication compared to others about urban art at that time?

I started to work on it during The Wall and Partizaning projects, because that time I collected so many information about history, but I also developed my own vision of street practices. Through events (lectures, discussions, festivals), since 2011, I started to write some articles which slowly transformed to a book idea. In 2015, I decided to publish it, but had no money for printing and started a crowdfunding campaign which was very successful. It gave me the chance to make it. I made a design, writings and asked permissions for pictures to artists and photographers, it was a big adventure for me and a lot of work which made me proud. I applied with the “Art and the City” book for prestigious awards of contemporary art in Russia and got the Kuryokhin prize in 2016 and was included to a short list in Kandinsky prize in 2019. That time it meant the first step of legitimization and recognition of street art practices by Russian contemporary artists, because before we had no books in Russia focused on this topic, especially approved for awards.

In 2017, you curated a group show and a lab in Berlin, which have been focused on Urban art and activism of Eastern Europe. Where was it, and how was the name of it? With which artists?

In 2015, I was invited to a Berlin conference called “Russland vs. Russland”, it was organized by Butterbrot duo, Berlin-based founders/artists: Sasha Goloborodko & Sasha Yurieva-Civjane. The Conference was focused on different confrontations inside Russia through artistic and activist practices. It was very important to me. We became friends, and they decided to transform the conference to a platform called “Coordinate system”. We started to work together with a wider perspective. No not only being focussed on Russia but also on Eastern Europe, including Ukraine, Belarus, Armenia, Macedonia, Poland, Hungary. The exhibition I curated in 2017 with Sasha Yurieva-Civjane happened in CLB Gallery in Berlin, called “New Urban reality”. The focus was on interdisciplinary street practices in Russia: we showed participatory projects from Krasnodar, some street artists from Moscow, Nizhniy Novgorod and Yekaterinburg. At the same time we organized Urban Lab in Berlin, for which we invited artists and activists from Eastern Europe. The program was focused on research about grassroots projects in Berlin. The final result was published a book in collaboration with MitOst foundation with texts of participants, it was called “RECLAIM, RECODE, REINVENT: Urban art and Activism in Eastern Europe”. I was the editor in chief of that book.

In 2018 you wrote and published the publication Russian Urban Art: History and Conflicts. How did Urban art change since then from your point of view? How did it change in Russia the last four years?

It changed a lot, I would say. Now in Russia, Urban art is more integrated to the white cube and became mainstream as visual art. People love it, because it’s easy to understand, colourful and good to have as a design object. In public space it’s grown by steroids (money) supported mostly by the government and are mainly abstract public sculptures or huge murals. For me, it is not so interesting. Illegal experiments are quite dangerous right now, because Russia is using some Soviet tools of repressions and censorship now. And what happened with Soviet artists who tried to do something non- official, I described in my book in 2018. Sadly, it is similar right now.

You are creating interventions in public space and in your book you describe the public space as a means of self-expression, and as a place to interact with an audience. Is it still the case?

It seems like it is not so effective as before. Social media and smartphones switched our attention from the street to the screen, and people are not so engaged as before. But it depends on the situation and the location, I guess. For me, the city space is still interesting to work with, because you can see so many different cultures, layers of designs, kitsch and advertising, and it is still a place to communicate with others. The street is definitely a very good space for experimenting in art.

Do you think public space changed in the last 10 years?

I think so. I see how Berlin was transformed, it looks not so poor as before I guess. I lived in Moscow for 20 years and I observed all the transformations of the city, which changed a lot in the last 10 years. It relates to political reasons, also in Moscow the money of the whole country is concentrated there (Russia is very centralized state) – it gives the privilege to realize ambitious projects. Nowadays, I can feel differences between Moscow, Berlin and Paris. In Moscow all services work much better (public transport, delivery, cleaning), but the city is too big to live there (population density, traffic jams, pollution) and definitely there is no freedom to self-express – everything in the streets is buffed and cleaned, for any political message you can go to jail. I would say now, there is better service for consummation for the price of freedom.

Does it affect your practice?

Yes, off course, in Moscow I don’t feel the public space as my space to work any more. In Europe right now I’m focused more on my personal thoughts because I have very fragile status here, something between immigrant and refugee without many benefits and rights. That situation is completely new for me, but I’m happy to have so many friends supporting me here.

You did a residency at ZK/U Zentrum für Kunst und Urbanistik in Berlin last year. On what project were you working on there?

I was at the ZK/U last year for getting a freelance visa. During the art residency, I proposed an idea about finding my place in the streets somehow. I prepared papers perfectly, but Immigration office didn’t accept my application and I went back to Russia. This year I came back to the ZK/U with my reflection of my attempt last year: I made a transparent suit as a skin (Migration skin) with many pockets in front filled with bureaucracy papers. This situation and my fragile status here turned me towards the topics of borders, bureaucracy, personal goals. And it seems like many people enjoy these works, because they had a similar experience.

How do you think the Urban art scene changed over the years?

I see how Urban art is more and more growing with murals. But this is not related to original Street art, I guess. No experiments there, it is used more as a city design. British curator and anthropologist Rafael Schacter declared the death of Street art in 2008. Spontaneously, I also did an exhibition about “death” at the same time, when it started to grow by „steroids“ and turned to muralism. Schacter also define the contemporary transformation of urban art going to the galleries or based on city contexts. In 2016, he called it Intermural Art, which could be also good definition. The term Post-vandalism by Stephen Burke and Larisa Kikol (Kunstforum Bd.287) is also a good visualization of the transformation of Urban art to something different. That is probably a more illustrative term of contemporary art based on urban contexts.

You mentioned this new term “post vandalism”. Years before the term post graffiti appeared. What is post graffiti for you?

„Post vandalism“ is quite new, it describes something based on vandalism, but it’s not about style writing, it could be related with graffiti but not only, it’s more interdisciplinary, I guess. „Post graffiti“ was declared in 1983. It was the title of a group show in Sydney Janis Gallery, and a documentary made by Paul Tschinkel in 1984. There were interviews with Keith Harring, Basquiat, Rammelzlee, Futura and others. There were also interviews with gallerists in New York. It was an attempt by art dealers to segregate artists from graffiti subculture, I guess. But the term wasn’t popular somehow, because some of those artists have not a real graffiti background and didn’t relate their practice with graffiti. Terminology in urban art is always complicated somehow…

Are there still street artists you find original and interesting today?

Most of the artists I can’t define as street artist, because street art today is more related with posters, stickers, stencils, murals, just images in the streets. I am still a huge fan of Brad Downey. We made many projects together and still work on it. I like the works by The Wa and OX, and good to see the transformation of practices to more participatory ones by Mathieu Tremblin. I like conceptual urban interventions of Wermke & Leinkauf, Epos 257, Vladimir Turner and Danilo Milovanovic. Actually, there are many different artists which I like, but I prefer interdisciplinary works at the intersection between vandalism, art and activism, social engaged art, site-specific and conceptual art, and with humor.

Thank you Igor!

instagram.com/igor_ponosov

Leave a Reply