ILLEGAL. Street Art Graffiti 1960-1995: Thematic exhibition and publication

The thematic exhibition “ILLEGAL. Street Art Graffiti 1960-1995” at the Historisches Museum Saar runs until February 25, 2025. To mark the occasion, the curator of the exhibition, Ulrich Blanché published a catalog of the same name in May 2024 with Hirmer Verlag. Featuring thematic contributions by five authors in German and English with illustrations of works from the exhibition and archive images – well-known and lesser-known works by precursors of street art – it names the protagonists who were artistically active in public spaces early on and around the world between 1960 and 1995. These include street artists and graffiti writers from the early days in the USA and Europe, but also gang graffiti in L.A. from the 60s/70s, for example, is not excluded. Visual artists who extended their artistic activities to the streets in the 1960s, particularly in France and the USA, are also addressed.

In addition, art historian Ulrich Blanché also devoted his research to modern artists who, from the 1930s/40s onwards, were already dealing with scratched and drawn graffiti on the walls of anonymous people and taking inspiration from them – such as the Hungarian photographer and artist Brassaï in Paris and his friend Picasso. Among other things, they ensured that graffiti became a topic in the art world for the first time.

Although the term street art was already used in the 1970s/80s for individual protagonists, mainly in the USA, it only became popular in the 2000s with the worldwide development of the phenomenon. The term describes illegally installed works in public spaces that are created two-dimensionally (or as sculptures) using various techniques and materials such as spray paint, paint, stencils, and paper works (paste-ups). Sometimes also by artists with a graffiti writing background, such as BANKSY. Non-authorized paintings or lettering on the street – graffiti – have a longer history, the beginnings of which are also covered here.

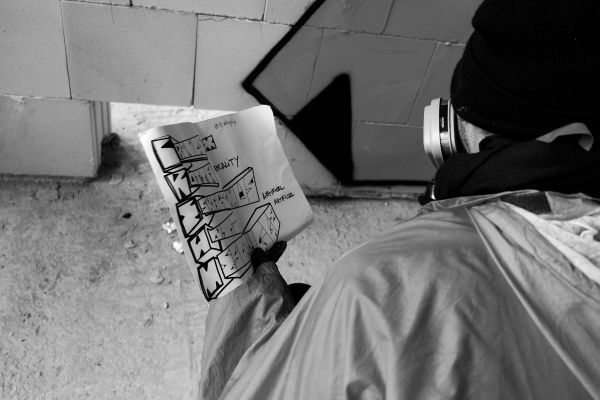

In “ILLEGAL. Street Art Graffiti 1960-1995”, the street art expert Ulrich Blanché has already dealt with preliminary forms from the 1950s onwards. In the introduction, he describes his intention with this exhibition and publication: “It is not the aim of this article to write a new, revised canon of urban art. The present selection of works is more of an offer to realign our perception of centers and peripheries via comparison, and via the examination of interactions and resonances. Instead of establishing a new street art or graffiti canon, the history of urban art outlined here below aims to question the graffiti-free canon of general classical art history, but at the same time also the usual, US-influenced history of street art as post graffiti.” The term post graffiti is used here in connection with street art, but was also used in the 1980s by gallery owners in the USA for works on canvas by style writers. Today, this term is used for the art that was increasingly developed by graffiti writers after 2000, which has moved away from classic style writing, partly detached itself from letters, and features other artistic forms of expression, stylistic devices, and aesthetics on walls and studio works.

In his introduction, Blanché first differentiates between graffiti, style writing/hip-hop graffiti, street art and urban art before going on to give a brief history of urban art from 1960 onwards. He mentions some pioneers from France, the beginnings of unauthorized art in urban spaces, the first tags and graffiti pieces in the USA, and their further development and manifestations in Europe from 1983 onwards. This is followed by descriptions of street art pioneers and their successors, as well as the last analogue generation from the 1990s, such as BANKSY. But the art historian Blanché goes even further back in history: early street art as art from 1952 to 1974 and the reference to the discovery of graffiti by modern artists in the sense of writings, scribbles, and pictures on urban surfaces. This graffiti served many modern artists as a structural model for art. Brassaï, Picasso, Desnos, Leiris, Prévert and others saw a particularly free, artistic quality in this anonymous graffiti. Brassaï’s photo book “Graffiti”, published in 1960/1961, plays a special role here. The entry of graffiti into art institutions from the 1950s onwards is also recounted here chronologically and is extremely informative. The Affichistes in France, the slogan “Bird lives!”, which appeared in the USA in 1955, slogans by SAMO©, the figures by Zlotykamien and the tags by CORNBREAD are also dealt with here by the author, who has been researching this topic for many years.

The other four authors of “ILLEGAL. Street Art Graffiti 1960-1995” deal with further topics. The German curator, author, and lecturer Johannes Stahl makes a contribution here on “Images and Words on Handwriting, Graffiti and Style Writing”. He researched and published books on graffiti back in 1989 and 1990. Frenchwoman Myriama Idir is a cultural manager, curator, and author who has long been involved with hip-hop culture and street art. She writes here a summary of the spread of style writing in the Grande Region in the east of France and west of Germany and the early networks with US pioneers. Certain regions of Germany at the border with France, such as the Saarland, where the exhibition is taking place, are given a special focus here. Players from Luxembourg and Belgium are also featured. German pioneers from Munich, Hamburg, and Berlin are briefly mentioned as well. In Berlin, Friedrichstraße station is referred to as the Hall of Fame instead of a Writer’s Corner: the meeting place for writers between 1989 and 1996, known as the legendary Corner Friedrichstraße. The term “Spraywerke/spray works” appears in the text on style writing in Lorraine for graffiti pieces on the line, an unusual term that makes us smile a little and reminds us that new terms in this subject area keep popping up here and there in texts over the years. These are usually invented by outsiders, by theorists, and not by the art makers themselves.

The following text on gender in graffiti and street art by Ulrich Blanché is very informative and mentions well-known and lesser-known female writers who have hardly appeared in specialist literature to date, such as Vampirella from the Netherlands or the street artist Jane Baumann, who sprayed stencils in NYC in the 70s/80s.

Author and art critic Jacob Kimvall from Sweden was himself a graffiti writer as a teenager and published a graffiti magazine back in the 90s. In his article, he takes a close look at the art of style writing as graphic design and marketing in the music industry. Images of record covers designed by writers and rarely published illustrate this parallel field of activity of some graffiti writers, who turned to graphic design as a career.

The author Sven Niemann’s contribution, “Academic perspectives on the phenomenon of political graffiti” is also very informative. Niemann limits his examples to a few cities in Germany. As a Research Associate for German Studies and Comparative Literature/Germanic and General Linguistics at the University of Paderborn, examples from Paderborn, Mannheim, and Cologne are mainly printed here.

This is followed by further specific, well-researched texts by Ulrich Blanché on certain artists. About the rather unknown tag writers Barbara62 and Eva62 in NYC in the 70s/80s, about works by the SAMO© duo Al Diaz and Jean-Michel Basquiat and by Keith Haring. The well-known street art pioneer from NYC, who died at a young age, was discovered in NYC as early as 1981 by the German art educator Klaus Wittmann, who contacted the art magazine ART at the time to draw attention to Keith Haring’s art. This correspondence and archive images by Wittmann are published here for the first time.

The comprehensive publication ends with a selection of archive images of works by various artists from different countries. Some are very well-known, others have hardly been mentioned so far. Some archive photos are not yet known from other specialist literature. For these reasons, this publication on the thematic exhibition on street art and graffiti from 1960 to 1995 is a very important art-historical contribution to the reappraisal of the history of this thematic field in the visual arts.

Information about the exhibition:

historisches-museum.org/illegal-street-art-graffiti-1960-1995

About the publication:

ILLEGAL. Street Art Graffiti 1960-1995

240 pages, 24 cm x 30 cm,

Softcover Language: German / English

Publisher: Ulrich Blanché

Publication date: May 2024

ISBN: 978-3777443591 Publisher: Hirmer

hirmerverlag.de/de/titel-3-3/illegal_street_art_graffiti_1960_1995-2585

hitzerot.com

190 views

Categories

Tags:

Leave a Reply