“born to graff. Graffiti in Marzahn-Hellersdorf”

Until March 5, 2023, Monday to Friday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. and every first Sunday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Bezirksmuseum Marzahn-Hellersdorf, Haus 1, Alt Marzahn 51

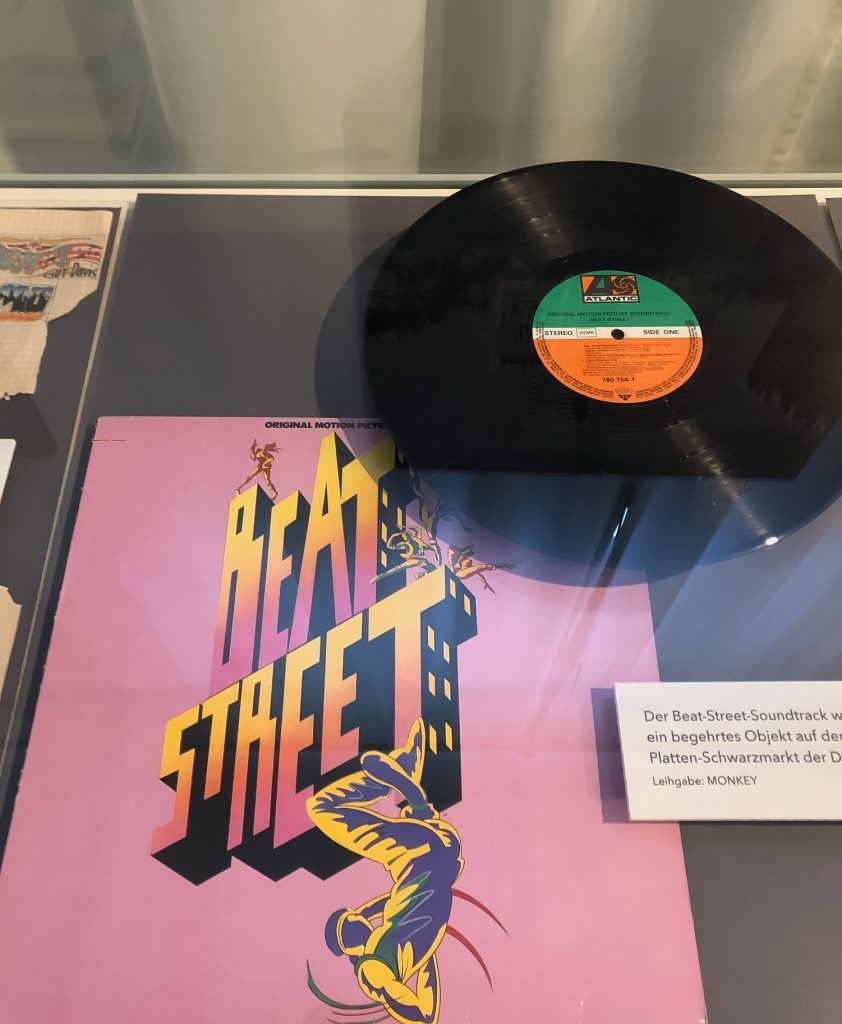

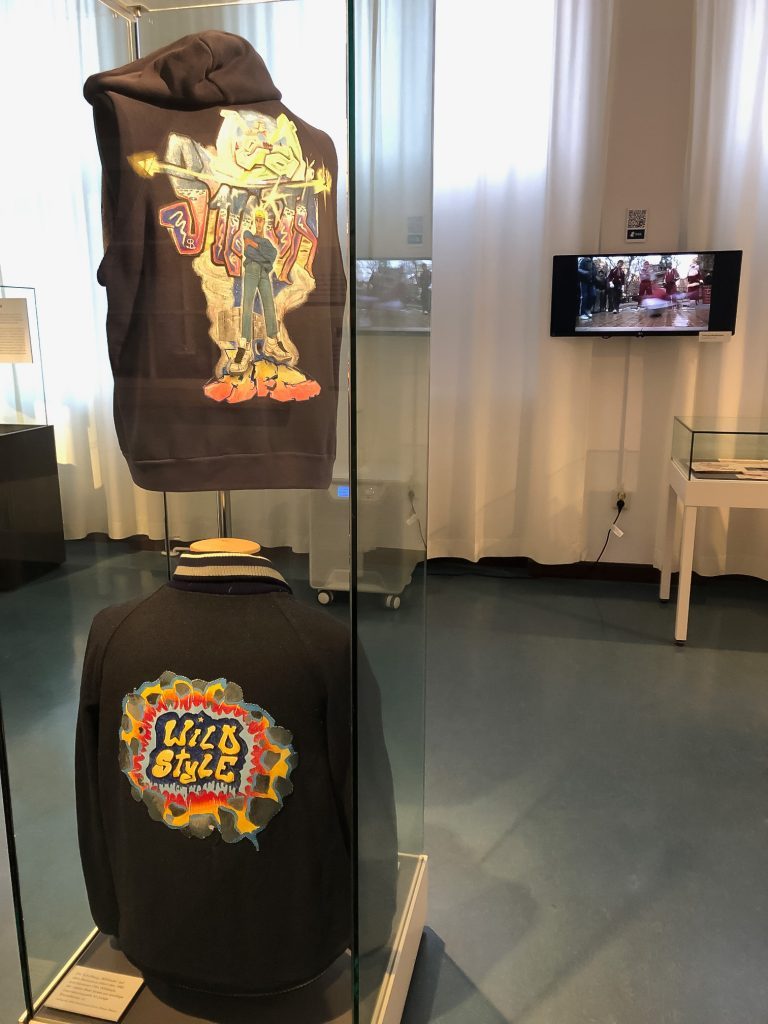

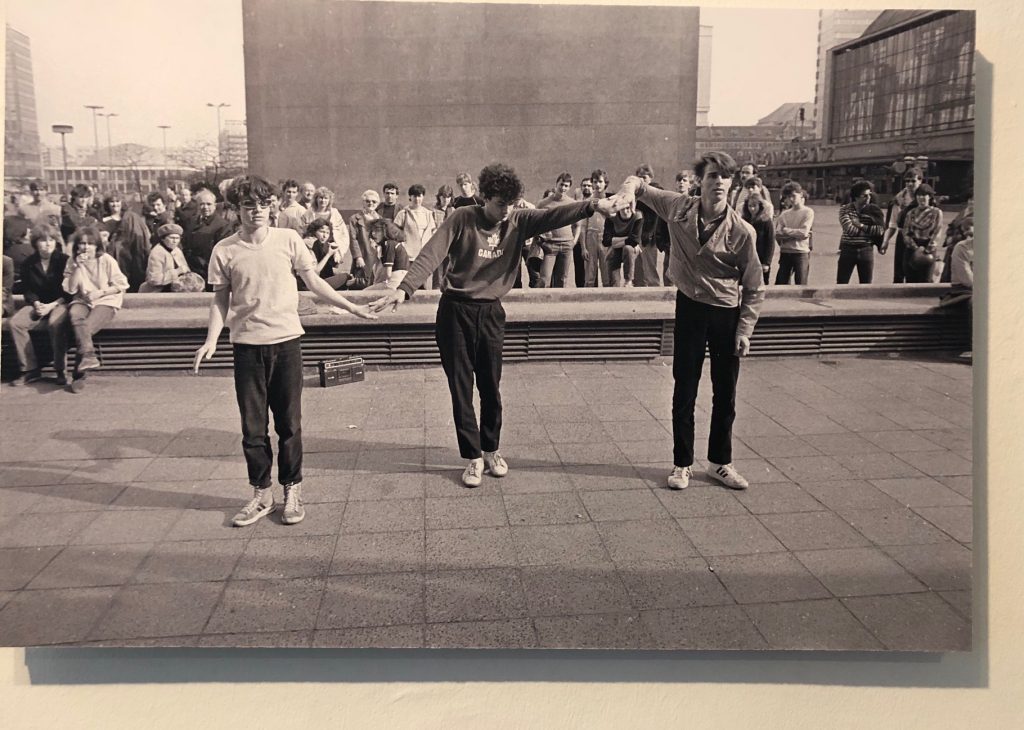

In the summer of 1985, the American movie Beat Street was released in East German movie theaters. The movie becomes a real success and ignites hip hop youth culture in the GDR, after it began in the West two years earlier with the film Wild Style, which was co-produced and broadcast on public television channel ZDF in 1983. Beat Street portrays two brothers and their friends growing up in the Bronx in New York. They are rappers, DJs, breakdancers – and paint graffiti. The first successful film Wild Style describes the story of graffiti artist Zoro, the tensions between his art and “real life,” and his relationship with his girlfriend Rose. The film also documents the emerging interest in hip hop culture by the media and the established art scene.

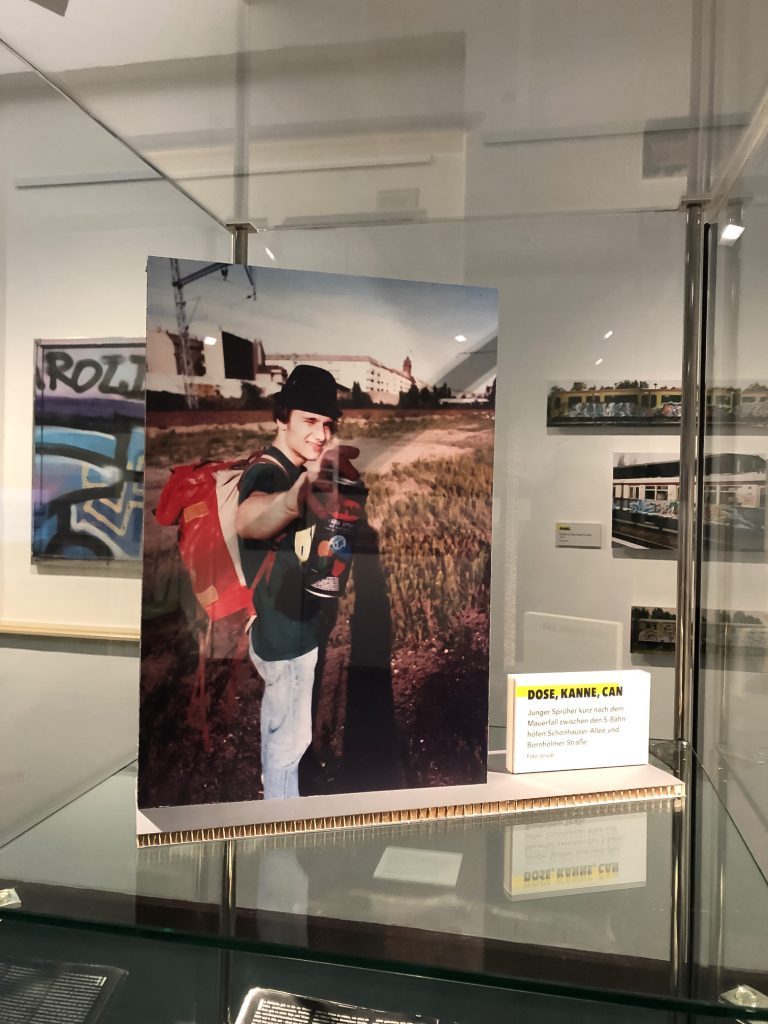

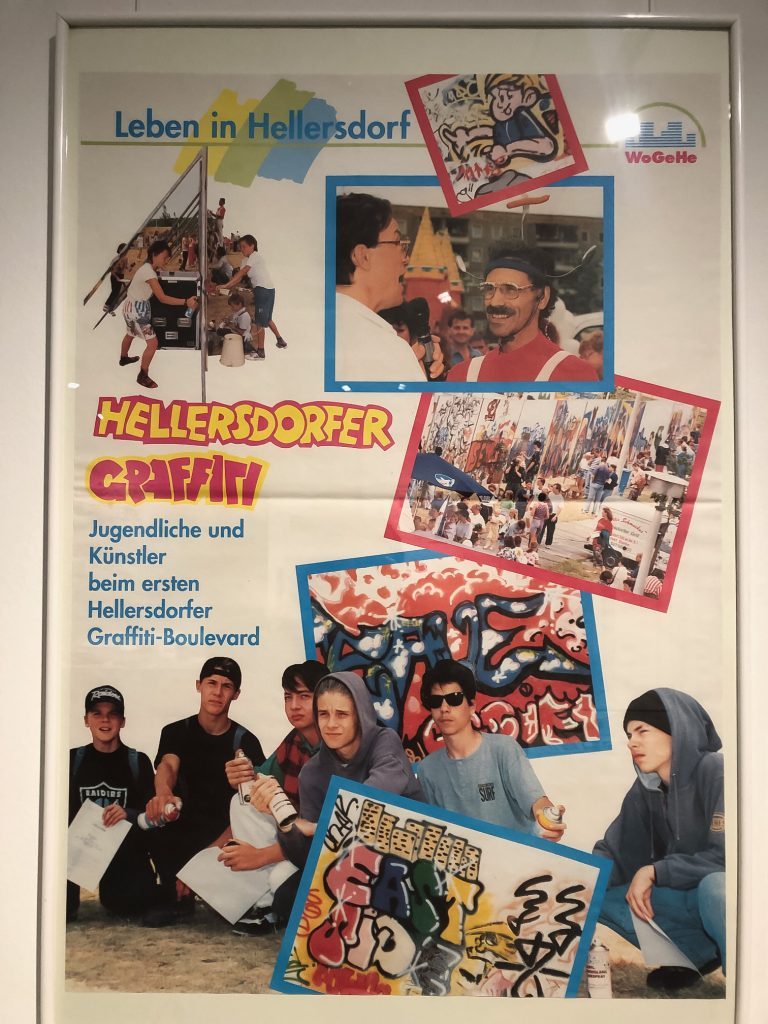

Through these films, the popularization of breakdance, DJing, rap, but also graffiti (style writing) as one of the four disciplines of hip hop, is unstoppable worldwide. A graffiti scene, which unites in crews and sprays on the streets, thus also forms in the east of Germany, however only after the fall of the wall. Before that, there were probably individual attempts here and there. The large districts of Marzahn and Hellersdorf offered the perfect conditions in Berlin in the 1990s: Countless gray concrete surfaces, families with many children, and youth on the streets looking for prospects and identity.

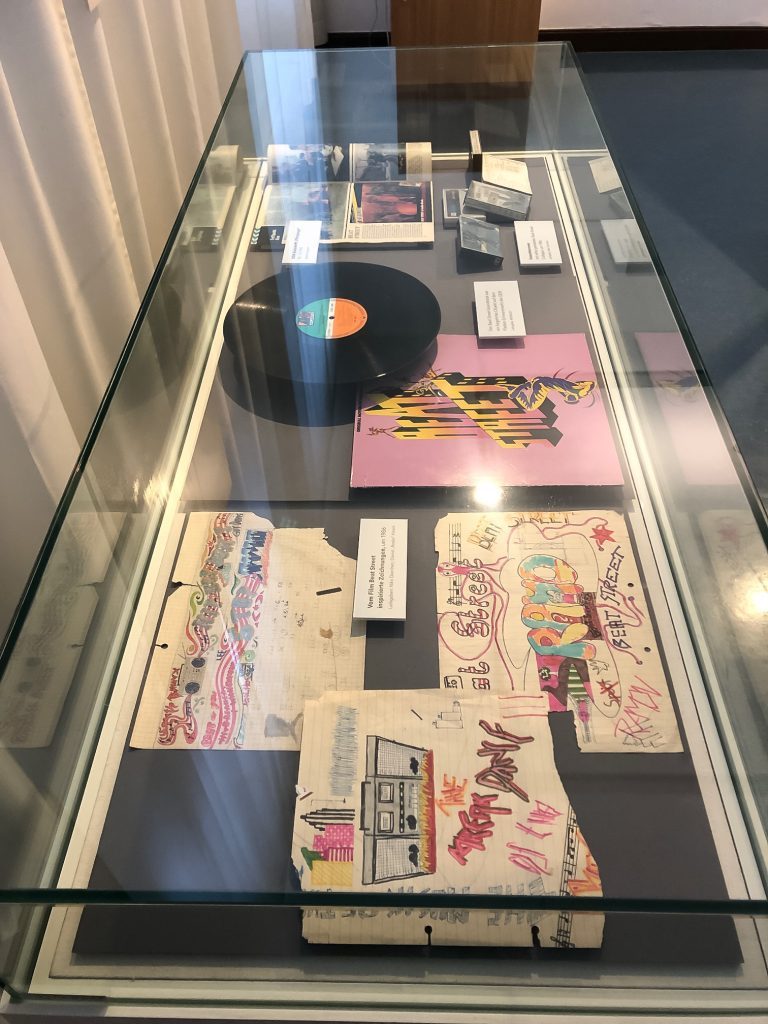

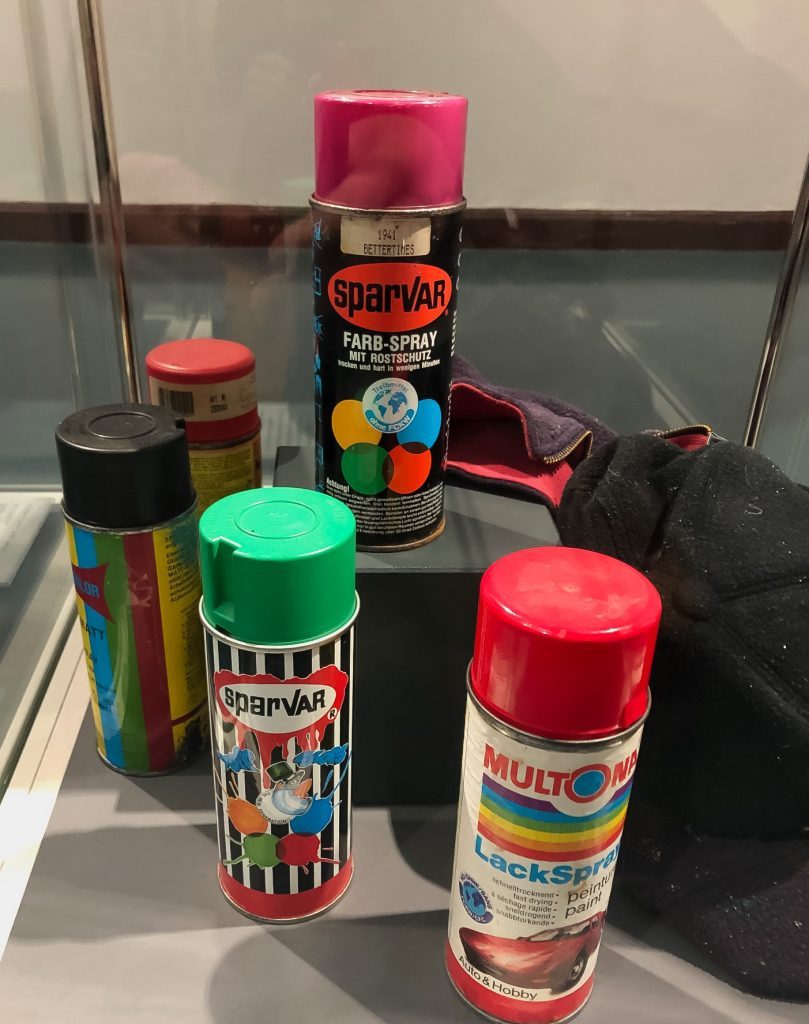

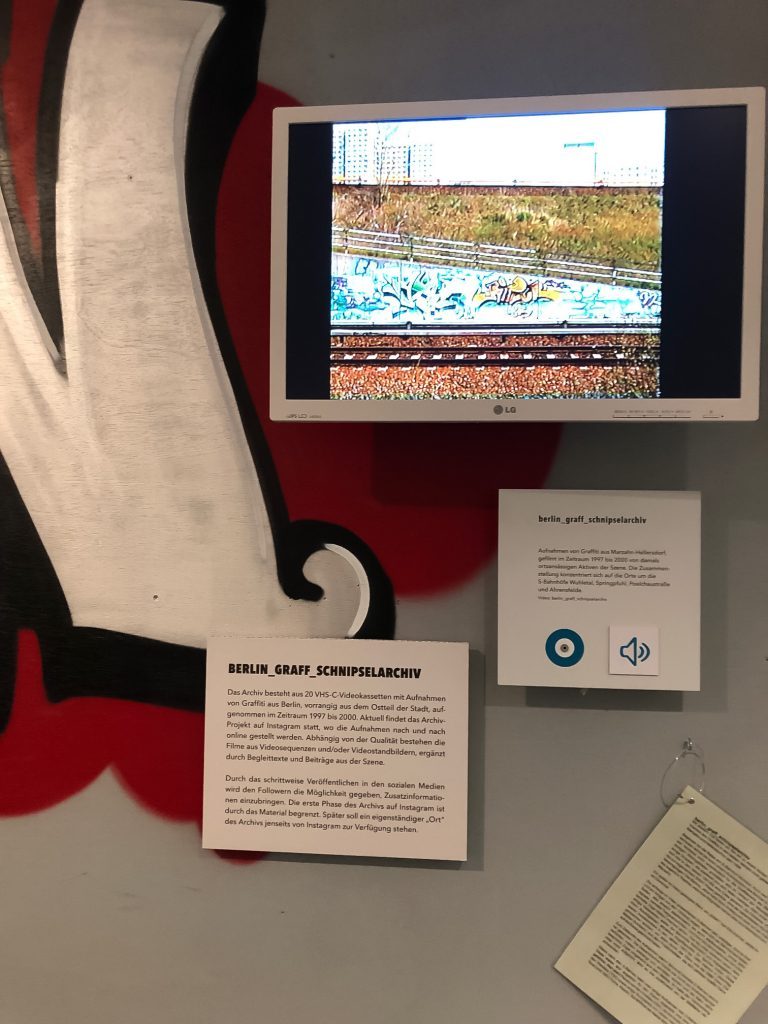

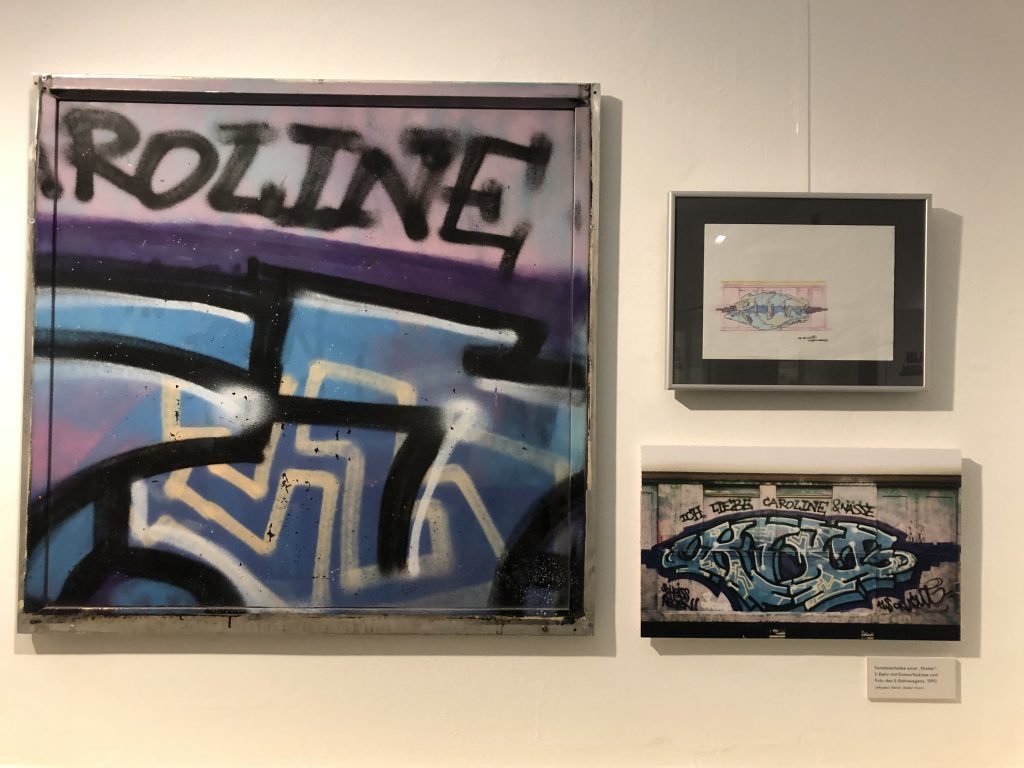

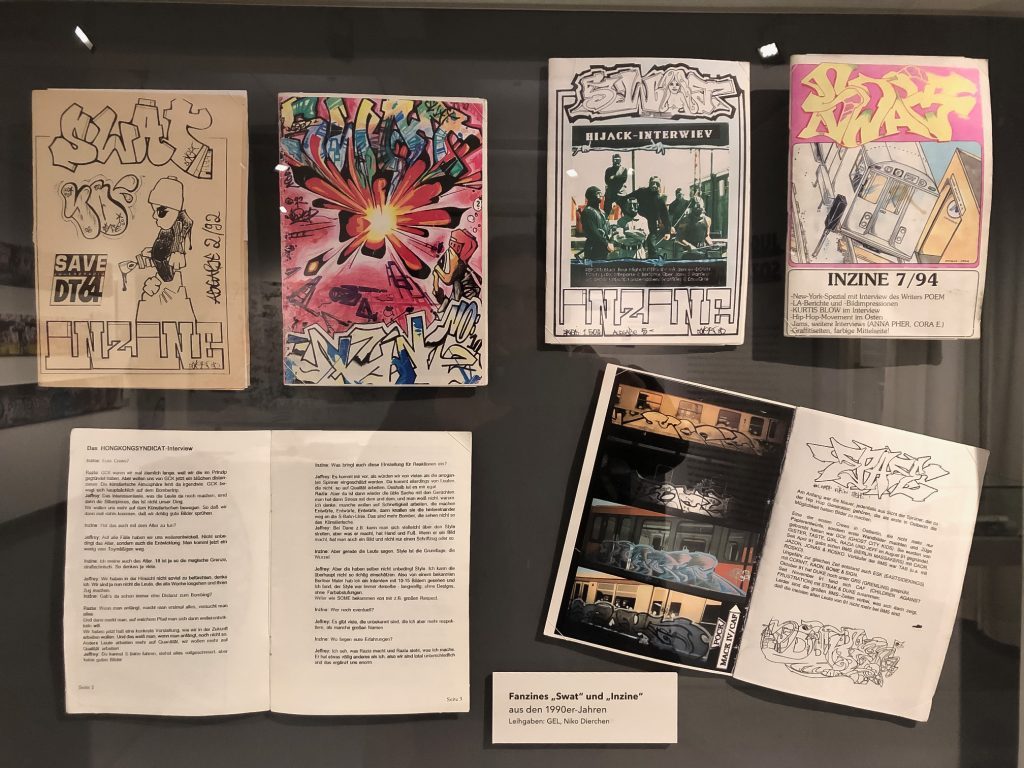

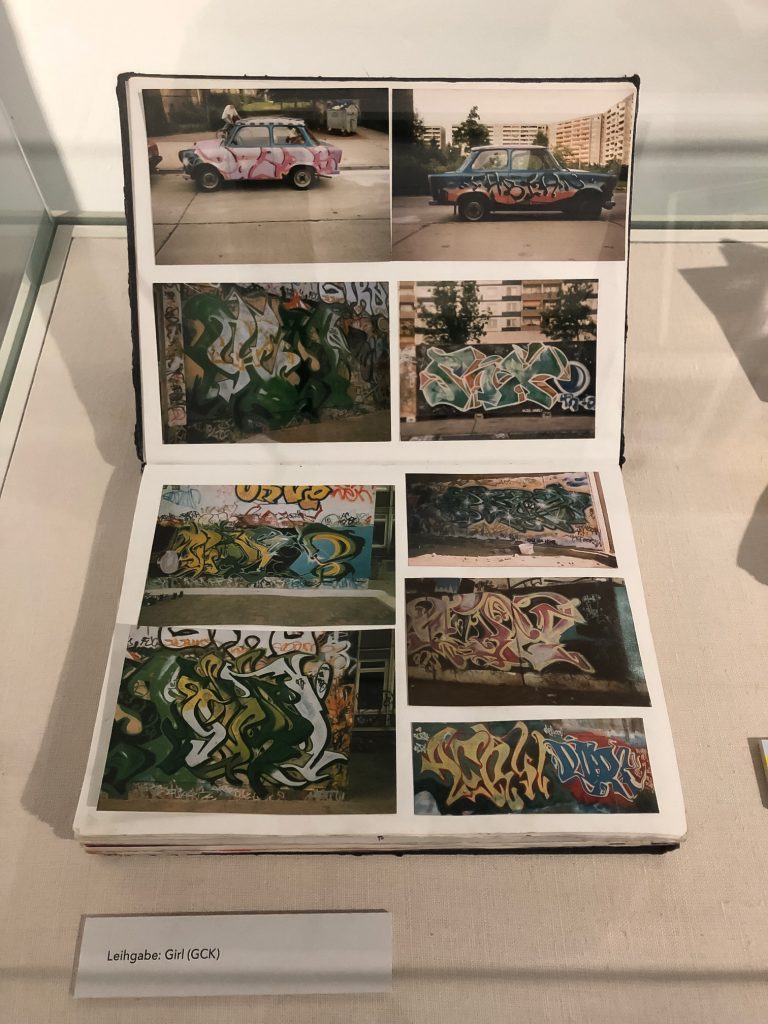

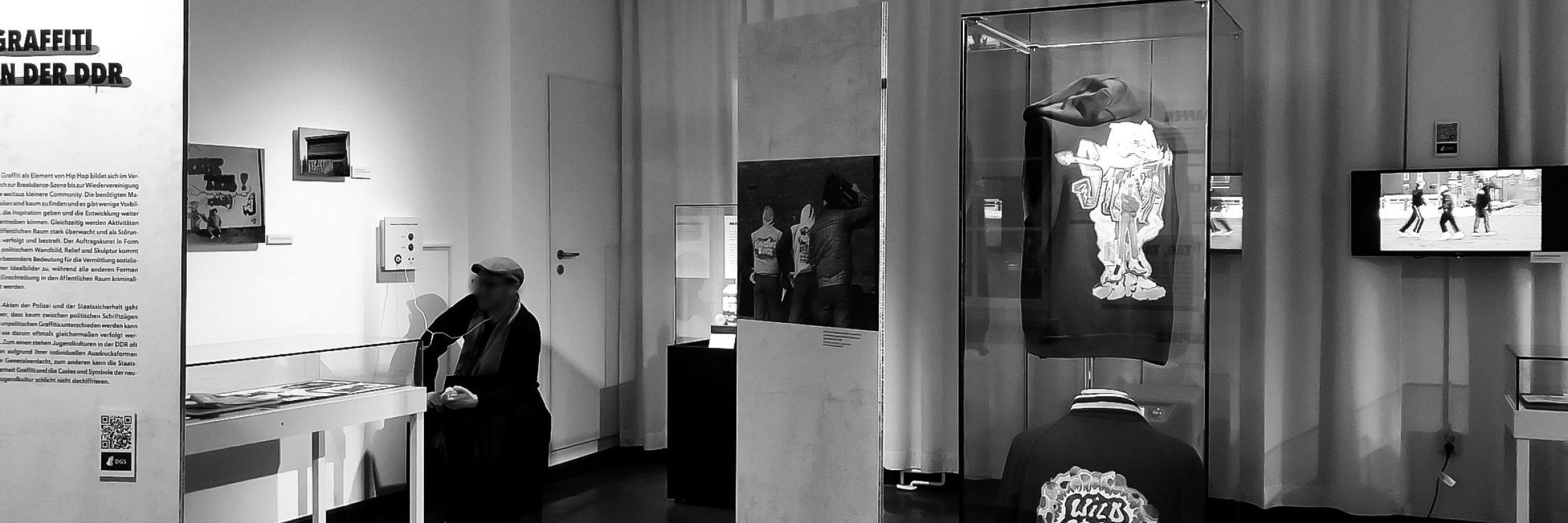

The exhibition #born to graff. Graffiti in Marzahn-Hellersdorf, initiated by the Bezirksmuseum Marzahn-Hellersdorf, presented in three rooms of Haus 1, and curated by Annika Hirsekorn and Niko Dierchen, tells the story of this youth culture in the district. Photographs show numerous graffiti pieces sprayed on walls in the district, along railroad lines and on trains. Some protagonists have their say in texts, audio and video stations, and original objects from back then, such as sprayers’ backpacks, backpieces on jean jackets, sketches, spray cans, records and mixtapes, revive the zeitgeist of the 1990s. Specific terms such as trasher (discarded train cars with graffiti) are explained on signs, and informative texts on large panels accompany the visitors through the exhibition.

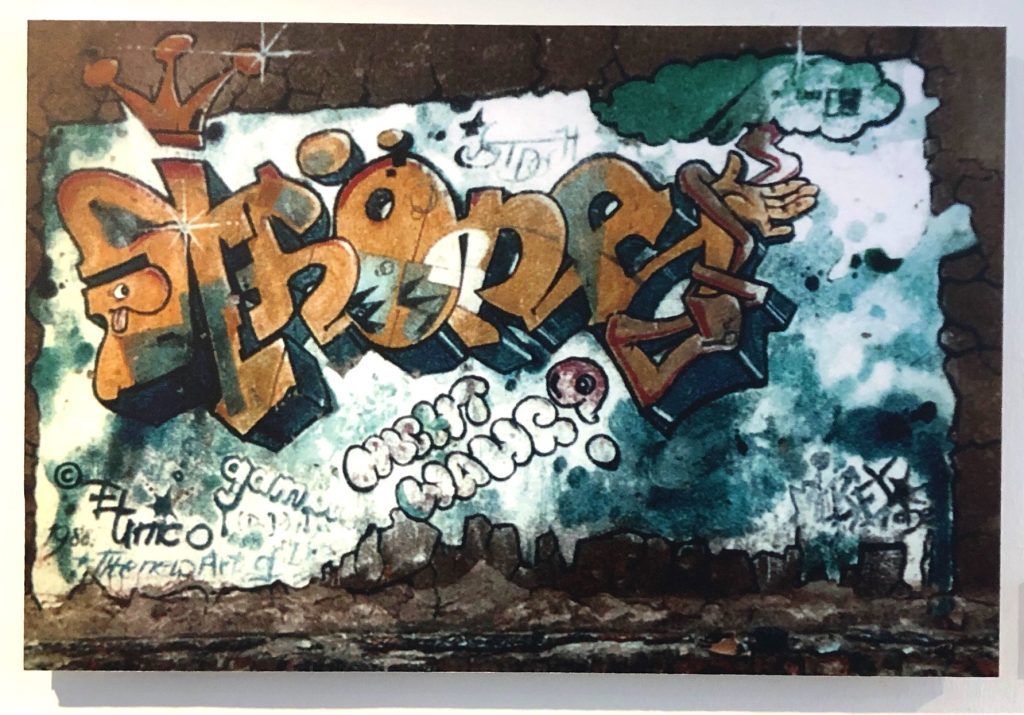

In the beginning, the young people in the East painted with shoe polish, because there were no cans to buy. But they didn’t get far with it. “The pictures disappeared in the rain – the shoe polish didn’t last,” recalls CORÌNT of Crew MIC from Prenzlauer Berg, heard in an audio station in the exhibition. The lettering that gives the exhibition its name, “Born to Graff,” a piece by MIC, was sprayed on a wall at the Greifswalder Straße S-Bahn station – probably one of the first graffiti pieces in East Germany. According to contemporary witnesses, the first graffiti piece in Marzahn was probably an “OZON”, but unfortunately the curators have not yet found a photo of it during their research.

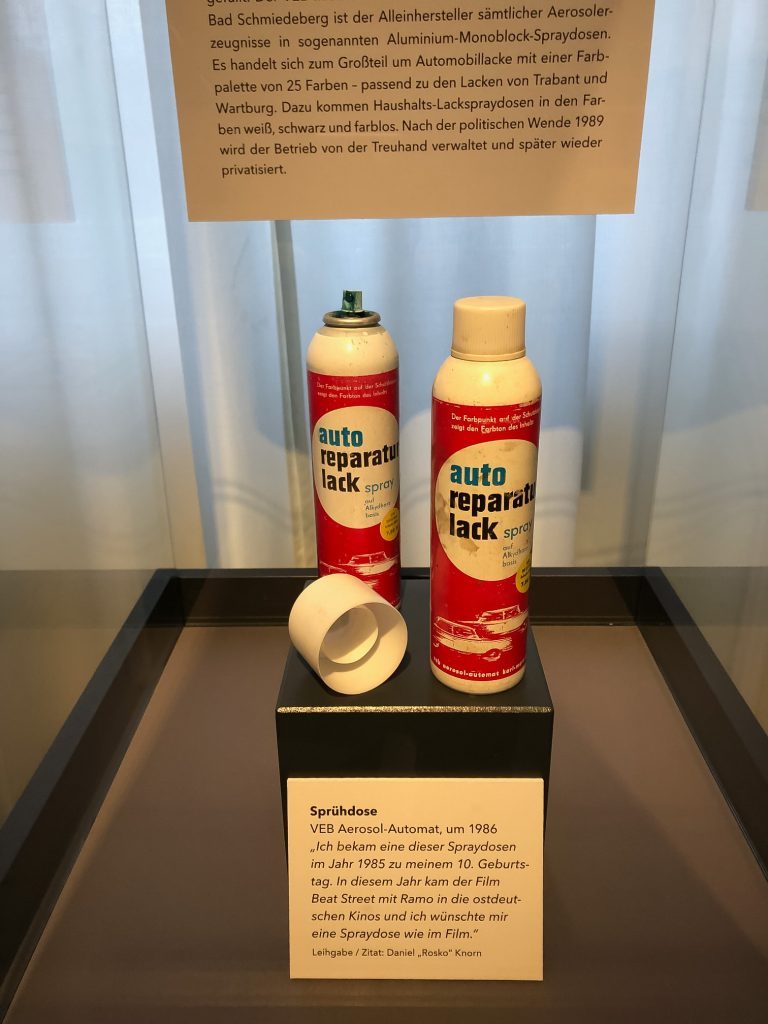

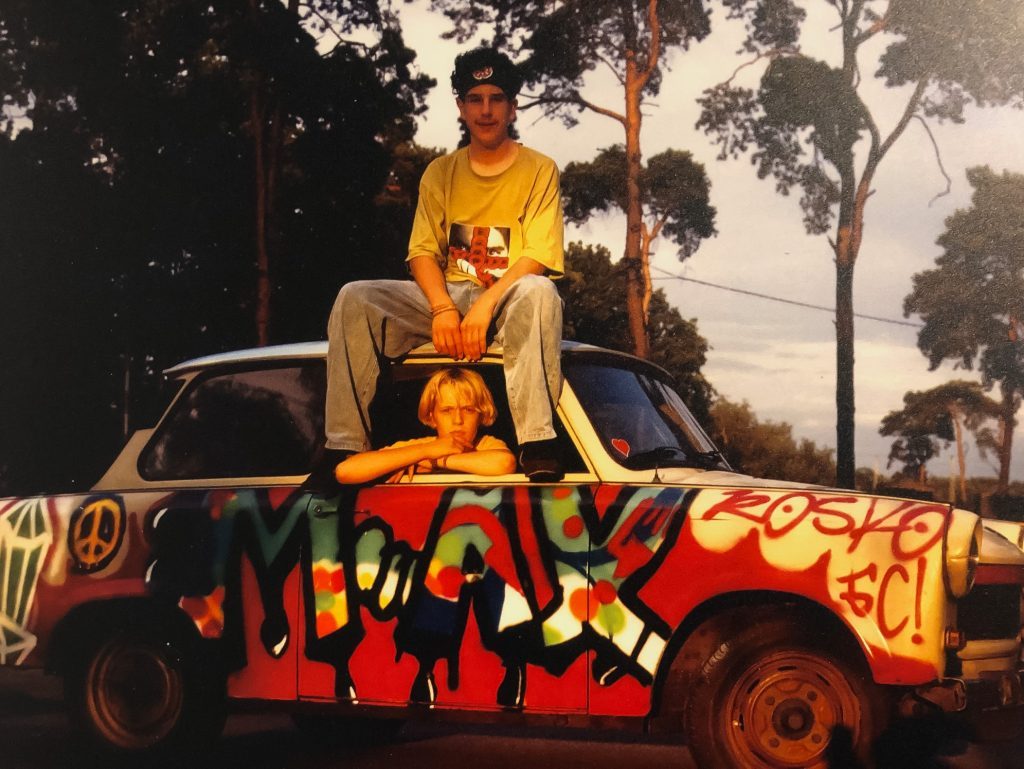

The writer CORINT tells how he was once approached by the police while he was painting. But graffiti was not yet illegal then, the police officers did not know how to react, whether it was meant politically or not. “I’m not done yet,” he replied, and was left alone. ROSKO tells in an interview that for his tenth birthday he was given car repair paint cans by his parents. He sprayed a heart on a lantern with it. At that time, there were only 25 different colors of this paint from VEB Aerosol-Automat. However, they were extremely hard to get.

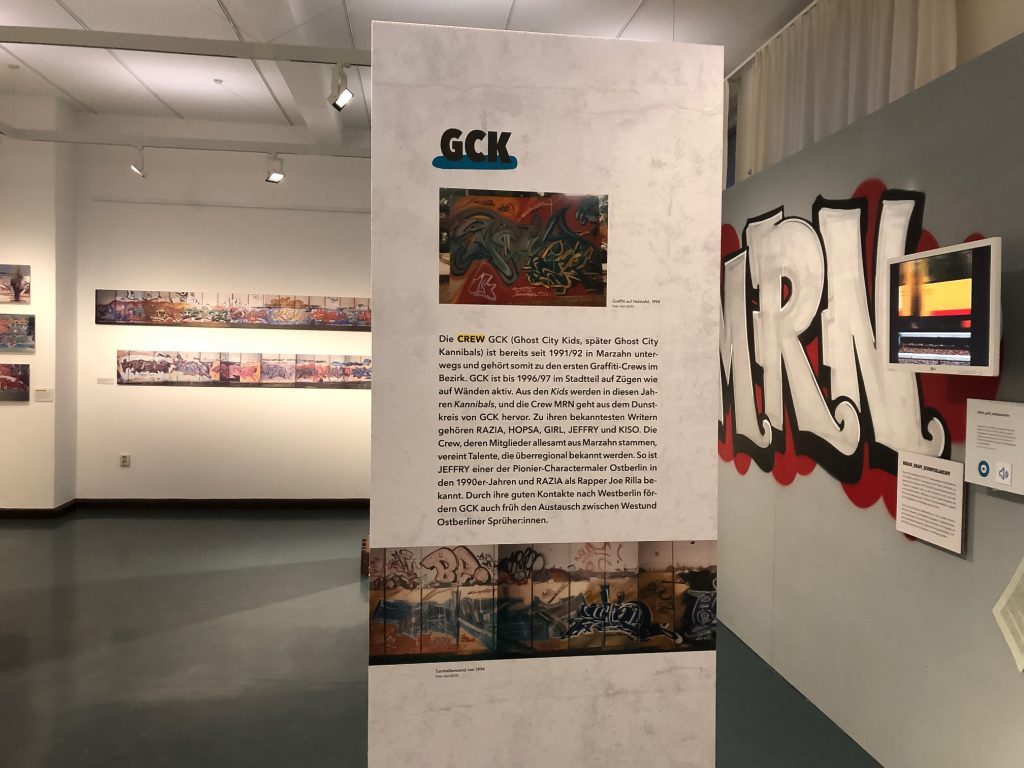

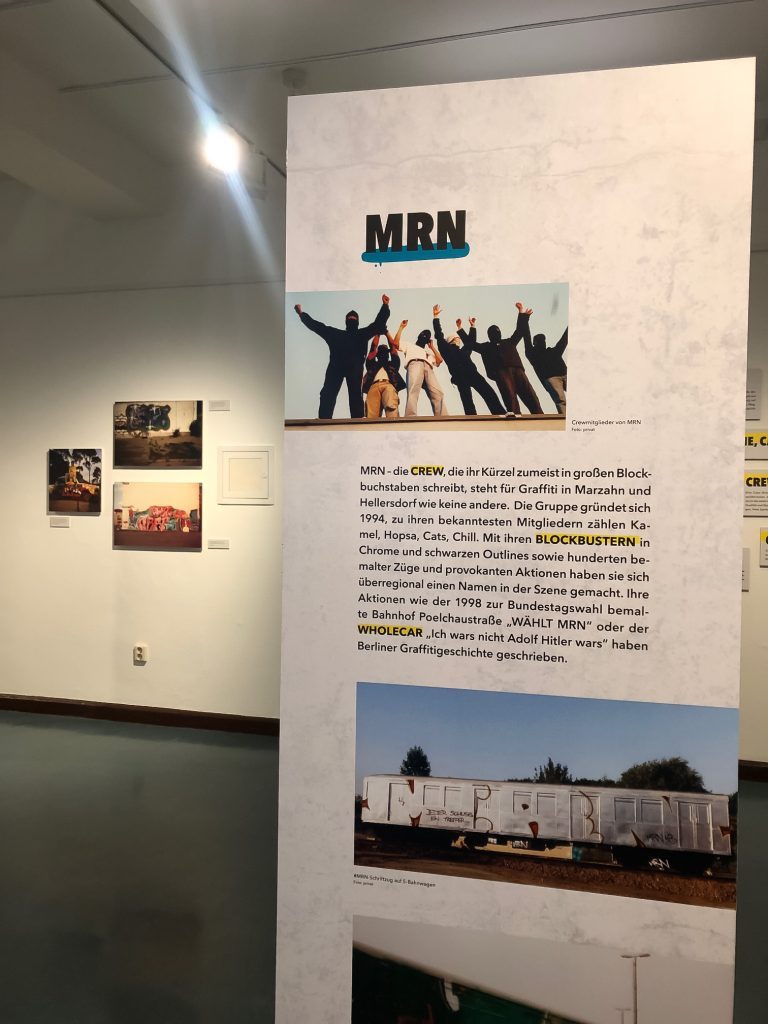

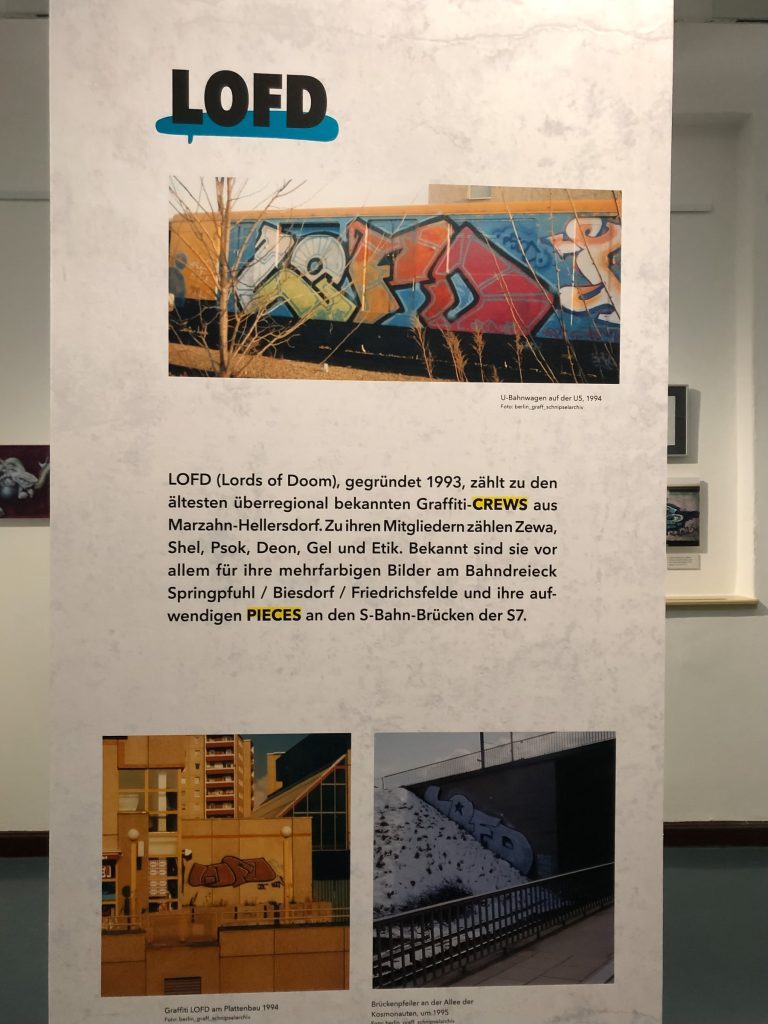

The young people sprayed against the gloom of everyday life, says one of them. He is referring to the gray architectural environment in Marzahn and Hellersdorf: tall prefabricated buildings, many gray walls. Janek at another audio station in the exhibition sees it similarly: “Marzahn had a certain charm of architecture. My buddy lived in an apartment that was cut exactly like my parents. He even had a painting hanging in the exact same corner as me. Graffiti for us meant breaking out of the system.” In fact, the district offered the best conditions: In addition to the high-rises, there were also long walls along the S-Bahn to Ostkreuz. “Marzahn was incredibly big, there were a lot of train tracks, you could get lost in the crowd relatively anonymously,” says Janek. A timeline in the exhibition shows when which crews were on the road in today’s Marzahn-Hellersdorf. The first ones are listed in 1991 and were called ABDE Boys, BAM and GCK (Ghost City Kids) or FMS (Family Shit). One of the oldest nationally known crews from Marzahn-Hellersdorf is LOFD, which was founded in 1993 and is still legendary today. MRN (Marzahn) only appeared in 1994, but then also made a name for themselves in the scene, known for their big bombings. Their members were called Alive, Chill, Kamel, Hopsa, Rebel, among others. In the 90s, other crews came to Marzahn and challenged the local ones. The 90s were a time of upheaval and uncertainty in Germany, and especially in Berlin. Hopelessness, unemployment, poverty, and violence were present and politically-oriented gangs of Neo-Nazis, left-wing radicals and others made the streets of West and East Berlin partly unsafe, especially for young people.

The exhibition makers Annika Hirsekorn and Niko Dierchen of this well-researched exhibition worked on this project for one and a half years, whereby important preparatory work had already been done with the previous exhibition 2020 “Klassentreffen Ost” at Neurotitan Gallery Berlin by Niko Dierchen, who is a sprayer himself in the 90s and today a tattoo artist. “Klassentreffen Ost” mainly showed photographs from 1990 to 2000 of graffiti throughout East Berlin. For this project concerning Marzahn-Hellersdorf, they had to search in their existing archive, as well as other private and Marzahn collections and talked to 20 protagonists from back then. In addition, the prehistory on the subject of hip hop in the GDR was reviewed here to tell the initial situation. In Berlin, in 2018, the photo exhibition SORRY!, later shown in Brussels as Berlin:Writing Graffiti, attempted to create an overview of the development of graffiti throughout Berlin from 1983 to the present, with the city’s transformation over four decades. Among the 600 exhibits, however, there was more archival material from West Berlin. Maybe it would be time to bring all archives together and show a big comprehensive thematic exhibition in Berlin in a bigger house, like Hamburg is currently doing: The Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte in the year of its 100th anniversary proudly shows the exhibition Eine Stadt wird bunt (based on the same-titled book published in 2022) and defines graffiti/style writing in the hip hop context as one of the most exciting chapters of recent cultural history. Berlin – with its reputation as the graffiti capital and a wealth of interesting historical as well as stylistic developments – would per se be the (cultural) city for a large thematic exhibition about the 40-year-old subculture, phenomenon, movement and art form graffiti/style writing throughout Berlin.

415 views

Categories

Tags:

Leave a Reply