Talk with photographer Marc Vallée / “Documenting Paris”

Photography, graffiti writing, street life and political dissent

Documenting Paris was a group exhibition and multiple publication launch hosted by the Retramp Gallery, Berlin in July 2019. The exhibition showcased Paris based work from photographers Marc Vallée, BadYear85, Thomas Von Wittich and Émilie Désir. Graffiti writers, Paris street life, train surfers and political dissent.

The London based documentary photographer Marc Vallée and initiator of the exhibition in conversation with independent art historian, writer and curator Katia Hermann on Sunday 28 July 2019 at the Retramp Gallery, Berlin.

“Documenting Paris”-Exhibition, ©mathieu brohan “Documenting Paris”-Exhibition, ©mathieu brohan “Documenting Paris”-Exhibition, ©mathieu brohan

KH: Marc Vallée! Nice to have you here at Retramp in Berlin!

Marc Vallée: Hello.

KH: So tell me: Documenting Paris is this group show of four street photographers.

MV: Yes.

KH: How did this happen? I mean, how did you meet and how did you have your idea to do this collective group show?

MV: Well, I met Thomas von Wittich two or three years ago when I had an exhibition at Urban Spree in Berlin. I met BadYear85 actually on Instagram. We liked each other’s work, following each other for two years and that led me to Emilie Désir and I was going to be having a launch for Down and Up in Paris here at some point and I got to meet all of those guys in Paris a few times and I thought I’ll expand it, I’ll make it a bit bigger, make it all four of us because I love their work; I am incredibly passionate about their work and I thought it would be just great to have all of us in one place and all the publications because we all come from the self-publishing, kind of DIY publishing background, and we found Retramp gallery via Larry Clark and here we are!

KH: So one question before we start talking about your work : I also wanted to talk about the work of the others because I had the chance to have a chat on Friday with Thomas von Wittich, whose work I already knew. Thomas von Wittich used to live in Berlin and he’s a photographer who started photography with taking pictures of street art in Berlin, that leads him to graffiti writing and documented some actions of Berlin Kidz. With this black and white series he got a break though I think, in the scene, and with high-quality prints he had shows in Berlin like at a gallery called Open Walls. I also talked to BadYear85 how did it start for him. He told me he is a graffiti writer, who used to do writing in a crew and started to document their actions, so that’s how he started with photography and from there he started to get more interested in street photography in general. Then, last year he created with two partners – the publishing house “Nuit Noir”, which is also self-publishing. I talked also with Emilie, who is more into reportage and street photography and she is the only one of the four photographers who is doing analog photography. All her photographs you see are analog. She is passionate about photography and she told me that she uses her camera, that she always carry with her, where she is. She started taking pictures of protest and demonstrations in Paris even before the Gilet Jaunes movement. She is really focused on the instant moments, because analog; you cannot take endless pictures, so she is really focussed when she is there, in the middle of people even in violent demonstration and situations, to do these amazing snapshots. So she is going more toward this political direction of protest action and the other ones are more following the graffiti writers at night or during the day. This is also what Thomas von Wittich told me: the difference with Graffiti writers in Berlin is that they are mostly active during the night, while in Paris there are many writers active during the day, putting their tags. This is what we can see in the exhibition. What you did, Marc, is you followed one graffiti writer for this series during the nighttime in a certain area of Paris. I wanted to ask you: how did you meet that writer and how did you do this collaborated work? How did you convince him to let you follow, how did you meet him and how did this series get produced?

MV: I mean, just one clarification: I don’t describe myself as a street photographer even though I take pictures on the street. My tradition is photojournalism and documentary, so it’s a little bit different. I don’t want to be pedantic but it’s a certain heritage. So this set called Down and Up in Paris – I stole the title from George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London – and the zine that is behind you on the window – it was all shot last November in Paris, on one night. Interestingly, I’d actually just met BadYear85; I’d been in Paris for Paris Photo and BadYear invited me to a party and I met Emilie for the first time and so this was last November and we all got very drunk and it was very nice. This graffiti writer in this series is actually from London (don’t tell anyone cause that’s a secret). He was in Paris at the same time I was and my history with him is interesting. There is a publication called Vandals and the City, which I shot and which was published in 2015. That was me following a young London graffiti crew for one year. He was the first one I met. It took me months and months and months – because I’m not a graffiti writer, I didn’t know any graffiti writers when I started shooting graffiti writers in 2010. So, I had to win trust, you know, they had to kind of check me out to make sure they could trust me. But when I was doing this, Vandals and the City he was the first one that finally got to me from that crew and we did the whole Vandals and the City stuff. Now the interesting thing about that work: it has been published in The Guardian newspapers, magazines around the world; it was in a big show last year at the Museum of London and actually for the advertising for the museum, for the exhibition a picture of him on a roof was the poster that was on all the tube station walls. So for a London graffiti writer, to have a picture of you on a museum poster that is as big as a wall on every tube wall across London and millions of millions – four million people travel on the tube every day in London, I mean – he was very happy. He kept on telling me he would tell various young women he was chatting up: “Oh, that’s me” and they were like: “Nah. you’re lying.” “Nah, nah, it is me!”.

KH: So tell us what kind of group show was it at the Museum of London?

MV: It was a group show called London Nights at the Museum of London and it had 50 photographers incredibly historic ones: Bruce Davidson, Bill Brandt… I mean, just, you know, a phenomenal amount of people and it was all about London and night. There were over 200 works in the museum. They bought the fibre prints, the limited edition fibre prints of my work for the collection, and then it went across the whole thing. So, yeah, so I am quite good friends with these guys now because I spent a year photographing them. They love the fact that there are images of them doing what they do is all around the world. So that’s cool. The story of this is really, he knew I was going to be in Paris for Paris Photo which is a photography fair in Paris and he came and met BadYear and we all hung out. We were literally just making our way back to the city center of Paris and he just started tagging and I just started taking pictures and it’s just a journey through the night. You know, just all the way through and he finished just about 5 am. It was brilliant because it was raining. Before I went to Paris I was hoping I could photograph some graffiti writers and I was thinking about Brassaï, the 1920s kind of imagery of the streets. This kind of – like this one, this is so Paris, it’s like a film set, like a film still, like a movie, you know. It’s all about the lamps, the lights, like in Film Noir. So it was literally about four hours work and it was an interesting conversation between him and me, because we don’t talk, really. I felt like it’s a dance. He’s tagging, he’s doing a throw up on a truck and I am just like following. When I came back to London I was like: “Well, there’s a zine here; I’ll make a zine.” I do the zines very quick. If I feel like I’ve got a set of images that work… I shot in November and then The Photographers’ Gallery in London launched it in March this year.

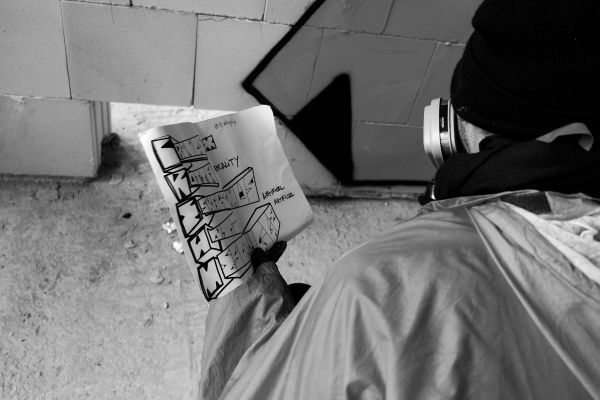

KH: So apparently, what we can see in the pictures is that you are interested in these graffiti writers – it is more about the act itself than about the tag or about the person because it is still anonymous, we can’t see his face, can’t really see his tag perfectly, it’s not a close up of the tags. So what is your interest in these actions of tagging at night? What is the mystery about it for you or the photographic interest?

MV: From the very beginning I wasn’t in fact particularly interested in the physical. I mean, I am interested in art-making and what tagging is – I used to paint when I was at art school so I have an appreciation but I have never, you know, even held a can. It was the physical act of them doing it. My general kind of discourse, view of my work is, I have been documenting youth culture for twenty plus years and I sort of frame it within – particularly in London – with the neoliberal city. So we have a critique on the neoliberalism, you know Milton Friedman, Chicago Boys, the Market is God, the whole neoliberal ideology, Pinochet in Chile, Thatcher in Britain, you know… Macron. It’s neoliberalism. Particularly in London – there is a lot of graffiti in London, but it’s very difficult to do graffiti at the same time. The security, the cameras, we have more surveillance, we are more clamped down. Paris and Berlin kind of feel like free cities for graffiti. Obviously, it’s illegal and people can get into trouble but it’s harder in London. That sort of puts up the idea of the rebel, the transgression, disrupting, claiming space. For me, I am putting up a political layer on their actions. They might turn around and say they’re just doing it because it’s good fun and they don’t give a fuck about whatever.

KH: But you seem to contextualise it.

MV: Yeah, I am contextualising it, I am contributing my view on them. But all my work has that kind of disruptive dissident, rebel, and it’s a bit romantic; I think these are a bit romantic in a way. There’s a kind of “against the system” but individually, so I like collective fighting but the individual can be a bit nihilistic in a way.

KH: You said you started in 2010.

MV: Shooting graffiti, yes.

KH: What was the key moment that you decided to?

MV: There’s a picture of mine from the Millbank Riots in London in 2010, it’s a bit like Emilie’s. The Conservative Party and the Liberal Democrats had come in to power, they decided to triple university fees per year from £3000 to £9000 and the students had mass demonstrations and then it all ended up at the headquarters of the ruling party, the Conservative Party and they smashed it up, it was crazy. I had been covering protests for about eight years. I worked for The Guardian newspaper and the Financial Times. I also worked as an investigative journalist for The Guardian for a long time as well so I use to write comment pieces about terrorism, press freedom, human rights and photographers’ rights particularly. Basically, I was sort of at the end, if I am honest. The amount of times you have your ribs broken or you’ve been smashed up by the police and I was put in the hospital by the police. You know, in 8 or 9 years of photographing protests – I was done. I wanted to move on. I was looking for something new. Also, I was looking at changing how I made a living. I was very much in the photojournalism route then. Working with newspapers, media organisations. Even though I come from an art background. I just wanted to dump it all, start self-publishing, go for print sales, galleries. I wanted to go a completely different direction. I wanted to go with different subject matter. I sort of fell into it – I was walking down this one street. There is this tunnel in London called Leake Street, it’s also called “Banksy’s Tunnel” which I don’t – I’m no fan of Banksy but – there’s a lot of graffiti there. I was just like “Oh that’s interesting” but I want to see the guys doing it, or the women doing it. I was like “Oh, the art is interesting, the mark makings are interesting, the tagging is interesting.” I really love tagging. I started speaking to people. I was hunting them down. I literally knew no one. I was like trying to find someone doing it and go: “Hi! Can I take pictures of you doing this?” And they are like: “Oh fuck off.”

KH: How did you get into the scene in London? Was it easy?

MV: It was relative. In a way, I can kind of thank the police in London. The amount of hassle they gave me covering protests for years. If you google me it’s easy. There’s all these big Guardian articles and stuff I’ve done on them doing bad things. I did this long term investigation on a secret surveillance database that was conducted by the Metropolitan Police in London on protesters and environmentalists. We exposed it all. Big front page thing. So that’s all out there. So if I go to a graffiti kid: “Well just google me. You’ll make the decision if you trust me.” Also because I sued the police for putting me in hospital, that helped as well. So, in a weird way, that kind of reputation, in that different area, they’ve decided to trust me. And when one trusts you, the second one trusts me. So basically, I got the Vandals and the City crew because of that and then that led in to everything else. And it just builds and builds and builds. So that’s why I could go and hang out in Paris and meet BadYear and everyone. It all becomes knowing each other. I had this with protests when the anarchist kids used to smash up banks at G20 protests in London. I got to know all them pretty well, through their Balaclavas. You can always see the eyes. You can recognise someone even if they are covered. They started winking at me, like: “Oh you’re here, okay.” They were winking at me also to tell me that I wasn’t gonna get beaten up by the anarchists. “He’s cool. He won’t sell the pictures to the tabloids. They knew I wouldn’t do that.” So then they would let me know, where things might be happening on a protest. That’s why I got good pictures of the protests because they trusted me as well.

KH: Let’s talk about your black and white photography. At the beginning you did also colour, you told me. You started with analog when you were an art student and then how did it develop from colour and black and white to what you do now?

MV: From the age of 18, for five years, I worked for a left-wing newspaper called The Militant. I was a typesetter and layout artist. That was in the ’80s until the ’90s. I am 50 years old. I gave that up and went to art school. I was a painter, oil paints. Then, in the first year, I discovered photography there and then I went and worked a summer camp in America at an arts camp for rich American kids. Like a summer job, between academic years. I was teaching photography because I was just being taught how to do photography so therefore I am teaching it. I started shooting punks and skaters because I used to be a skateboarder and I was processing film there in America all through the the summer and just printing and printing. So it started off being youth culture because I was young and skating – I knew all those cultures. Then, when I was back in London, I did an awful lot of stuff around the queer, alternative scene in London. All that work is on my Instagram. The Martin Parr Foundation is currently scanning all my 90s negatives of all the queer boys in unbelievably 90s looking fashions that look very much like they could walk down the street now. You’d would not think they were 21 year ago.

KH: But these are in colour?

MV: Yes, these are the big colour ones. I had a studio in East London, I had a darkroom and I was printing colour. I could handprint colour and I was doing these beautiful prints and I really know colour. I think that comes from the painting. My art teacher said I was a great colonist but I was a terrible drawer. I couldn’t draw. I was crap.

KH: Sounds more like abstract painting.

MV: Yeah. My colours were good. So why would someone who is a great colourist end up in black and white, that is the question! It was quite practical. At the beginning I was like, I’m gonna shoot this graffiti stuff and I’m going to do this self-published zines. It was cheaper to do it in black and white than colour. That was partly the reason. The second reason was, I’m a huge collector of photography books. All the Japanese photography books, all the inky black, it just blow me away. And then you look at Brassaï and I thought it’s going that way. The pictures I was shooting to the destination of the publications… it kinda worked. Nine years later, Down and Up in Paris is in its twelfth or thirteenth publication and they are all black and white.

KH: You are interested in collecting books and photographs. Are there some photographers that inspired you, that you could say “I am very inspired by these classical photographers”? And also some that are specialised in documenting the graffiti writing scene?

MV: Yeah, I mean anyone who shoots youth culture will probably mention Larry Clark. I was this kid, after my first year at art school, working in America, shooting skaters and punks in 1995 and one of the other people working there, one of the Americans, said “Oh you should check out this guy called Larry Clark. You’re shooting stuff like him.” And I went and checked it out and was like “Oh wow, yeah.” You look back and he’s done Tulsa in ’68 and it was like wow. It blew my head off. I was just like, this is what I want to do. But it was nice that I was doing it already before – it was that classic reference of someone very nicely going: “Go look at this.” Cause that’s what they’re doing. So Larry Clark is huge for me in that way and obviously, his work was here just a couple months ago.

KH: That’s how you discovered Retramp.

MV: That’s how I found this gallery, yeah! Because of Larry Clark and Jonathan (Velasquez). Jonathan was in Wassup Rockers, Larry Clark’s film and he was the boy he photographed a lot so I met him in Paris. I met Larry Clark at the gallery that represents him in London, the Simon Lee Gallery. I own Larry Clark prints so yeah, that’s a huge one. With the graffiti, it has to be Martha Cooper. The great, great, absolutely bow down Martha Cooper. I really like her Play (ed.: Street Play) stuff that she did when she was still working on the New York Post in the ’70s, she used to go to whatever job she had to do and then she would have a couple of shots left in the roll of film and she would cruise through Alphabet City and the East Village and there would be all these kids jumping off buildings and smashing stuff and in fact playing. So she would get these pictures and that book is absolutely amazing. But then, she made Subway Art which is the definitive book on graffiti, which actually took that graffiti style, the New York style of graffiti to around the world.

KH: Did you ever meet her?

MV: Yeah, I met her. Yeah, she’s cool.

KH: So, you are also interested in public space. Public space, private space, neoliberal city. So do you think this is coming from the London situation?

MV: There is a zine I did called Anti-Skateboarding Devices which is all sold out now. There were three editions. You can see it on the website. It is basically about little bits of metal that places put down to stop people skateboarding. I’m sure everyone has seen it. In London, it’s everywhere. So I just went around and photographed absolutely low, shallow depth of field. Everywhere you could think, there they were. Obviously, as an ex-skater, I knew what they were and that, particularly in London, the public space, the realm is being effectively privatised. I’m sure it is happening in parts of Berlin and all around the world and maybe not as extreme. For example, City Hall in London, where the Mayor’s office is, the seat of London democracy – the physical land is owned by a Kuwaiti investment fund and its next to Tower Bridge. You think you are in a public space but you are in a private space. And that’s where all the anti-skateboarding stuff is. If you try to take a picture with a professional-looking camera they’ll stop you. The tourists with an iPhone can take a picture of Tower Bridge. If you try to have a political protest outside City Hall without permission, they’ll kick you off because you are on private land. So there is this whole privatisation, within the neoliberalism of the whole society, but it’s the physical space they are trying to disrupt. I like it when kids smash off the anti-skateboarding devices. Skaters always fight back, you know? So that zine was all about that. And that was in The Guardian as well, that went everywhere and that became a thing. Then they had lots of anti-homelessness spikes. I don’t know, I haven’t seen them in Berlin.

KH: No, not yet.

MV: So you’d have these spikes outside of windows, shops, to stop a homeless person sleeping. Horrific! They can’t just sleep on the street in a safe, not wet bit, cause it’s inside the shop. It’s defensible architecture and it comes from the Broken Windows ideology, where a lot of academics to the right have projected this idea that if you see a lot of graffiti and a broken window you’re gonna get drug dealers and then you’re gonna get rapists and then you’re gonna get…

KH: But you can see it doesn’t work in Berlin because the houses are full of tags and bombed and they’re not empty at all. People are living there.

MV: I mean, people may not like it, but it’s not creating the crime zone.

KH: No, apparently not. Not here.

MV: But in the UK, it’s seen as that. Its government policy, its local city policy, it must be clamped down, it must be driven out, it must be stopped. So, the idea of disrupting or taking space back is seen as a very serious threat. To capitalism. So that’s what it is.

KH: Do you think graffiti writing has a political function?

MV: I can think that, but obviously all the writers will have different views and different politics and do it for different reasons, but for me… particularly in London, yes. Elsewhere it might be different. I think we can appreciate it purely aesthetically. But I’m not particularly interested in any artwork purely for aesthetics. I want: why was that picture made, what is the story, what is being said, what are they trying to communicate? Not to say I can’t adore abstract expressionism or the Dada movement, surrealism, but they all had meaning. I mean, surrealism was politics, you know. Left-wing politics at that.

KH: So what is gonna happen with the show? Is it going to travel and where can we find your prints or prints of these photographers to buy?

MV: All four of us have donated the images to the gallery and anyone can have one for a donation to Verity, to Retramp gallery, to support this amazing, wonderful space. This is kind of interning and I have to be a bit careful about not being a hypocrite for this bit. I would never think of selling these because these are just paper and it’s for this wall and this exhibition here. I do sell limited edition fine prints that are in museum collections and in private art collections. The last solo show I had in London, an important art collector came and bought the whole show.

KH: So where can you find the prints? Online?

MV: They are online. If you want to buy a print you go to the website. The prices aren’t there, you have to email for the prices. You’ll get a reply. That helps fund the work. And also, of course, there are the zines at ten pounds. You can see the work on the internet, you can buy a publication for ten euros, you can come to an exhibition like this and see it for free, you can go to a museum and see some of the work in a museum but if you’re gonna actually buy the high-end prints, that’s obviously a lot of money. I am selling that to the rich people and they are funding me being here. I think that’s a sort of democratic way of doing it. Exploiting the capitalists. Or becoming a capitalist, I don’t know.

KH: To give back to the base, right?

MV: Well, yeah. I come from a DIY tradition. I was a punk, a skater, I love doing DIY shows, but I also want to pay for my apartment and go to nice visits to Berlin and Paris.

KH: So tell me, how did you get the idea to first do this show Documenting Paris in Berlin and not in London or in Paris?

MV: Okay, you really wanna know?

KH: Yes!

MV: So, one of my friends who actually isn’t here told me: “Are we going to go to Berlin Pride this year?” Because we usually go most summers. So I was like: “Yeah.” She goes: “But you’re not going to put on a show, you’re not going to do a launch?” “No, no, it’ll just be a holiday.” I am incapable of going anywhere without putting on a show. So we were booked already, just a group of my friends just to come for Pride. Then I ended up – in a show.

KH: Do you have an idea where it might travel to?

MV: This is going to go to Paris next! Considering the other three have just gone back to Paris a little while ago. We’re going to do it in Paris. I’ll just come from London on the train.

KH: How is the situation in London? Is it easy to find a gallery?

MV: Yes, we’ll find a space in London. We’re going to do London next year and I think we are going to expand it. I don’t think we’ll be doing the same work, I think it will probably be Paris based but it will just be new Paris work. And London is alright. You are all lovely people but in London I can fill a room. I like the idea that it is going to roll. So basically, think about it, I met Thomas von Wittich once at a launch here, I met BadYear85 online on Instagram, and we’re all hanging out and got drunk and then we’re here with this show. And now we’re going to tour and we’re all close friends, we’ll keep on doing it. I think it’s like a collective now. We were very democratic. When we hung the show yesterday it was democratic chaos in here, when we decided where everything would go. How could we not, with Emilie’s work, you know? People fighting.

KH: Do you have an idea or image or desire to do a Documenting Berlin one day?

MV: Yeah, I did a Berlin zine a few years ago called Tiergarten Transgression. It’s a queer anarchist kid walking through the gay cruising ground in the Tiergarten. I came here for a conference that was at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt. There were some German academics that were around the conference that was called Tiergarten, Landscape of Transgression and was looking at the Tiergarten from history, even the plants were transgressive towards each other, it was about everything. I went to one lecture about the gay cruising ground and I went to go find it afterwards and I happened to be with a queer anarchist and we just walked through the Tiergarten and we naturally just found it. I said, “Well, let’s just go for a walk” and we took some pictures and found it and made it into a zine. It’s really weird because it’s very different from everything I have ever done, that one. The more conceptual art side of photography really loves it. The British Journal of Photography did a big thing about it, there’s a thing called Self Publish Be Happy, they’ve done stuff on it. It’s a whole section of photography. I am documentary and more didactic, I think, that’s more non-didactic and they love that one publication. I don’t even think the images are that great. There are a couple of images that are quite nice; it just about holds for 12 pictures for a zine. I did it more as a thank you to the conference. I did it as a response to going to the conference. I thought it was really fascinating, a conference about the Tiergarten. I’m obsessed about the Tiergarten. So maybe I’ll come back and shoot more Tiergarten.

KH: One last question from my side: Train writing, as the king discipline of graffiti writing, has never occurred to you to follow up?

MV: It certainly has. If you are a graffiti writer, or if you are in crew and you are painting trains you can get pictures of that, a lot easier. Also if you are not gonna put your name on it. I’m me, I am Marc Vallée. The police know where I live. I don’t want them to knock on the door and seize all the computers. So when I was shooting Vandals and the City, the first really big one, the London one. I’m a member of the National Union of Journalists in the UK, the journalist union, the trade union, I saw their lawyers and said I am shooting this graffiti, I wanna do the trains and they are like: “Ugh” Because the British transport police are like, evil. Even though I’ve got a UK Press Card and I’m a member of the press, if I went onto the tracks it would be criminal trespass. But here I am in Berlin and I am very close. There are people who would want me to do it with them, I am just trying to work out how I can do it with them. It’s the one thing that’s left. I haven’t done the trains. I gotta do the trains. Martha’s – how old is Martha? – she gets to hang out with 1UP for a week?

KH: And what about the rooftops?

MV: I love climbing roofs. That’s great, yeah. Vandals and the City has got roofs!

KH: Okay, thank you so much for answering my questions. (To audience) Do you have any questions to Marc? It’s really great to have such a known photographer from Great Britain over here.

MV: Not so “Great”.

Audience member: You must be taking a lot of pictures during the night, over months and years. How do you decide which of them you want to show? Do you know in the very moment you take the picture?

MV: Well, it’s interesting. Do you know Willian Eggleston, the American photographer? Very famous colour photographer? He always had a problem with editing. The story is that he only shoots one picture of the one thing, so he doesn’t have to choose between them. I don’t do that. I think I shoot maybe two or three frames. I don’t think there is too much science to this. I think, for me, if I am like this and I am like gasps. If my mouth drops, I think that’s the one. Cause there is something going on in there. If I get that kind of feeling. For every one of these, it’s a gasp. This one here? That was that moment. And the framing: I am the same distance away in pretty most every image. If you look at the whole zine it’s like that. That is a conscious decision. I wanted a big frame. I wanted the street lights. And I wanted you to know it’s in Paris, especially altogether in the publication.

Audience member: Do you see a difference in writing on public spaces versus writing on private spaces?

MV: No. There are two of my publications. There is The Graffiti Trucks of Paris and The Graffiti Trucks of London so a truck is private property and obviously, you can look out the window, so I don’t see a difference in the context of legitimacy. Obviously, the owners might feel more aggrieved than maybe a public institution or vice versa. I don’t know. There’s a question. When I was shooting, I spent all this time shooting trucks in London and I did get to speak to some of the owners. Some of them are market stall owners and I did speak to them and they were like: “Why did they do it?” I said, “do you like it?” “It’s Okay.” So, I don’t know. It’s anecdotal but maybe like: “I’ve got a new van, it’s completely white, and now it’s not.” Obviously, that’s upsetting for them. But, you know. I am ambiguous, I suppose.

Audience member: You told me about your printing process. You shoot digitally but you print analogically? Can you tell me more about that?

MV: When I first started I shot on film. I’ve always printed black and white or colour. I was kind of late switching over to digital. I switched in about 2006. That was mainly because I was doing the protests and that’s also because I had to hit the picture desks. You know, laptop, protest, pictures bang, gone. It was part of the profession. The interesting thing with Emilie is, she’s shooting all of this on film, she’s not hitting newspapers, she’s doing it for another reason, so it’s different. I think sometimes your reason will change your technique. These are all shot on a digital camera. A very nice one, that’s gorgeous. It’s little. But the high-end prints that I do, they are all fibre based paper, so they are physical fibre based paper, and even though it’s a digital file, the paper goes through the chemistry and it gets processed as a print.

There’s only one place in the whole of the UK that does that. They work with me, I have a good relationship with them. Some of the Graffiti truck ones, the London and Paris ones, for the show I had last year, for the solo show, we also printed some onto metal. They were really quite big (get’s The Graffiti Trucks of London). This is Drax. Drax ran with King Robbo, who had the big war with Banksy and they made a documentary about it. Drax came to the show. Once he saw this picture of his stuff on the metal, he was the happiest man in the world. He’s my age; he’s old graffiti writing. I got this nice picture of him in front of it like that. The curator wanted me to spend money because they were paying for the printing, which was quite handy for the show. I was like, well, the writers are writing on the truck, why don’t we print on metal. I didn’t want it to be cliché, I didn’t want to be gimmicky. But it did work. You could bash them and throw water on them, because the fibre based prints you could not do that. But even then you can see the street lights were there. There’s always a process, it keeps on going.

Notes:

Documenting Paris

Down and Up in Paris

Down and Out in Paris and London

Vandals and the City

Writing on the wall: inside London’s graffiti scene – in pictures

London Nights

Rewriting the city

Millbank and that Van

Revealed: police databank on thousands of protesters

Anti-Skateboarding Devices

Tiergarten Transgression

The Graffiti Trucks of Paris

The Graffiti Trucks of London

Marc Vallée: London & Paris 2011-2018

BadYear85

https://www.editionsnuitnoire.com

https://www.instagram.com/emiliedesir/

https://www.instagram.com/thomasvonwittich/

312 views

Categories

Tags:

Leave a Reply