Kouka, the intercultural contextual artist

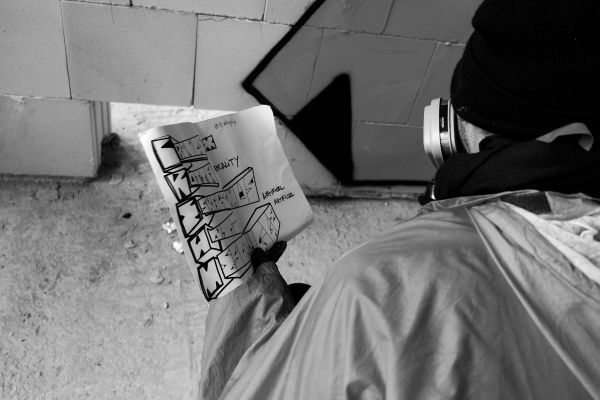

Born into a family of artists from France and Congo, Kouka Ntadi was born in Paris in 1981 and moved to Toulouse as a teenager. At the age of 14, he discovered graffiti culture through colorful works by crews such as Truskool and began tagging and painting pieces with his pseudonym Blam. As a skater, rapper and writer, Kouka is a representative of urban cultures. With his roots in graffiti and with the advent of street art, Kouka belongs to the generation taken by the street art wave of the 2000s. During this time, he studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Avignon, where he experimented with video and media images before starting intensive painting in Brussels in 2003 during an Erasmus exchange. Using spray cans and brushes on large cloths, he painted after photographic images from the media and decontextualized their meaning. The influence of the photographic image is still present in his work today. In 2005 he moved back to Paris, where he still lives and works in a studio of the city of Paris.

Symbols of the universal human being

His well-known motif of the Bantu warrior, he now paints since ten years again and again. On a trip to Gabon and Congo he painted his first warrior in 2008. Graffiti did not exist there, public space did not exist, there was a lack of materials for painting. In a library in Libreville, he discovered a book about the Bantu peoples, ethnological black-and-white photographs of warriors and hunters, anonymous, in neutral poses. They inspired him, and he painted his first Bantu warrior with black and white wall paint on an abandoned building in Libreville, which was to become the International Center of Bantu civilizations in the 1980s and has served as a training camp for the French army ever since.

Since then, this image of the Bantu warrior has served him as a universal symbol of mankind, who opposes life with an inner strength and courage, represents values and appropriates public spaces, territories, in order to protect them. The figures painted in black and white, which stand like statues on walls, are meant neutral and universal, without ethnological or colonial context, without allusion to war or aggression. As close guardians of humanity with their presence in public space, they are meant to hint at the universal in man: his strength and his transience. In addition to the male hunters, Kouka also paints female ones, following the example of the Amazons of Dahomey.

But apart from models from Africa, Kouka has also incorporated Western models into his work, such as Rodin’s thinker. In his search for further symbols of human existence, he came across the thinker. Naked, without cultural attributes, muscular and yet vulnerable as a person who thinks about his existence, the sculpture was created by Rodin as the guardian of the Gates of Hell, this role model also became a symbol for universal human beings for Kouka.

From painting on the street, on walls, his figures also migrated to the studio. Instead of taking classical prefabricated canvases, Kouka searched for other more natural surfaces for his painting and since then has used wood, cardboard, paper glued to canvas, or raw canvas. On some works he integrates his rap texts, forms his words with the spraycan and uses them as a graphic element next to his figures.

Montresso Art Foundation/Jardin Rouge, his second home

Kouka makes the artist residence at Jardin Rouge of the Montresso Art Foundation in Marrakech this year for the fifth time. During his first stay in 2014, the place was not completely finished. There were mainly Russian artists and a few Frenchmen. Kouka worked there with an artisan/joiner to learn how to work wood and then use it as a base for his painting. He made friends with the owner of the Jardin Rouge and came every year since. In 2015 he worked there on the content and representation of the warrior, the following year he created totems.

This year, during his three week stay, he used sackcloth as painting ground. These he got at the local markets and stand for him as a symbol of the triangular trade, travelling, and have their own story through traces and travel stamp marks. He sees a connection with the Bantu people who were shipped during slavery. This time he is not depicting male warriors but female warriors, to whom Kouka dedicates a series. As if zoomed in, excerpts of female body parts are depicted, such as belly or breasts, which are regarded as universal symbols of femininity and fertility. Kouka deliberately wanted to pay homage to the power of woman and femininity. His new works can be seen at the Montresso Art Foundation until 13th of March.

Intercultural roots

Today Kouka works 80% of the time in his studio and only accepts a few commissions in public space, sometimes he intervenes unsolicited. He has also been to Berlin several times and painted with Miss Van and visited his friend SP38. He left behind several warriors: in Wedding, on a piece of the Berlin wall and at the East Side Gallery between 2014 and 2017.

The artist is critical of the currently used terms such as urban art and street art, which many use arbitrarily without having any background knowledge or making distinctions. In his opinion, many young “street artists” are “artificially” created and act in public space for strategic marketing reasons in order to serve the market. The once political, rebellious and anti-system spirit of a counterculture has become a market culture. Many institutions make use of this label and exhibit artists, but in most cases, the makers have no relation to these cultures. Even in France, where galleries and institutions have been advertising these art movements for a long time, there is, in his eyes, no adequate place to mediate adequately. As a successful event for the mediation of the graffiti culture, he names rather small formats that emerge from the scene, such as the festival Planeta Ginga in Rio, which was initiated by Assassin’s MC Rockin’ Squat.

For these reasons, Kouka – who comes from the graffiti culture and the street art era-, who has European and African roots, defines himself as an intercultural visual artist who makes contextual art. However, he still follows certain practices of a graffiti writer: exploring urban space, perceiving and reading graffiti and finding ideal spots. And from time to time, he feels like painting a spot, in order to place his painting in a spatial and temporal context, visible and as a symbol for all people.

400 views

Categories

Tags:

Leave a Reply